Play deep!

There's a league-wide movement to position defenders deeper across the spectrum. Do the Royals follow the trends? And how does it impact keeping runners off the bases?

It’s generally accepted that a league-average BABIP is .300. While that’s close to being true, BABIP is not a cookie-cutter statistic—some players have a skill profile that lends itself to a higher than average BABIP., others don’t. On the Royals, Michael A. Taylor has a career .330 BABIP. The flip side is Carlos Santana who has a career .249 BABIP.

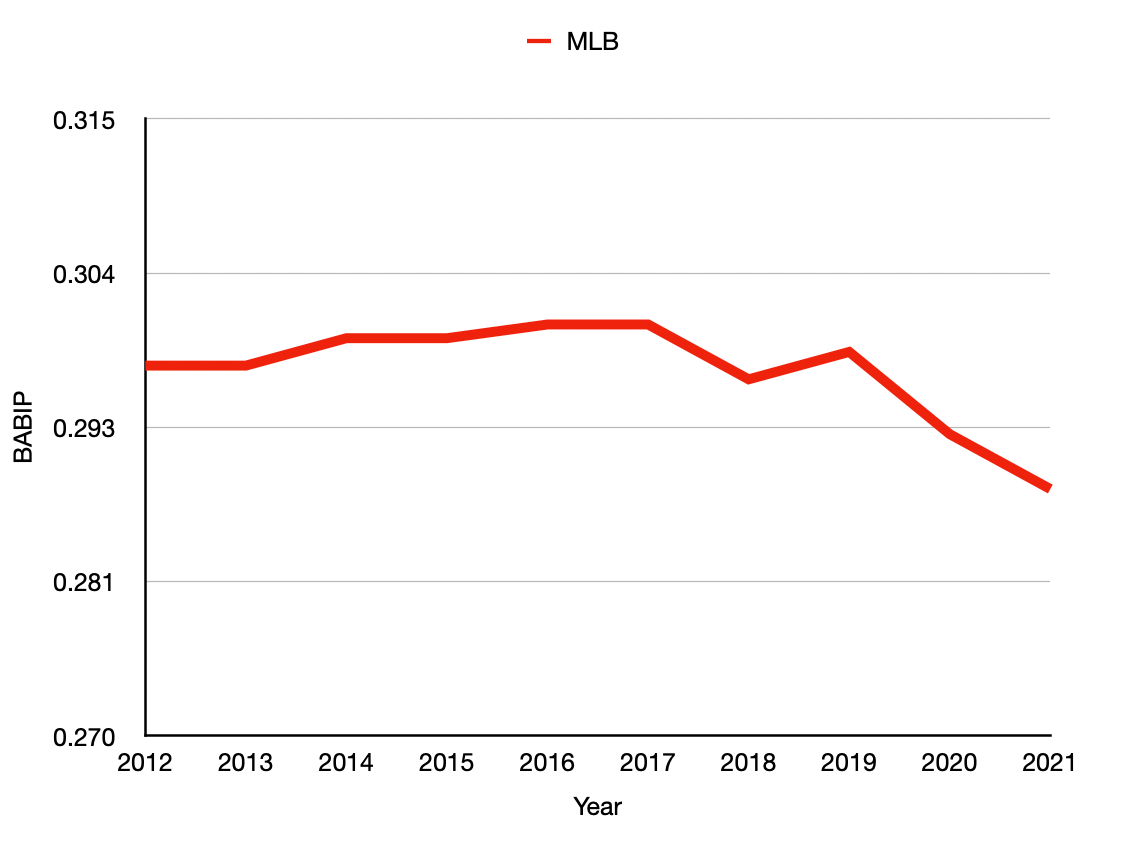

Still, when talking about the MLB—the league—as a whole, a .300 BABIP is generally a good jumping-off point. Or at least it used to be.

In the last 10 years, BABIP has fluctuated very little from season to season, always below .300 and usually within about .004 or so. That’s changed dramatically in the last two seasons.

The league BABIP in 2020 was .292. This year, it’s all the way down to .288. It’s an incredible decline from what we saw in the last decade. Obviously, last year was the Covid-shortened season. Things were weird. Although BABIP takes a while to stabilize, even in the shortened season there should’ve been enough batted balls in play for there to have been a solid data point.

We’re just about at a similar point a little over two months into the 2021 season and BABIP is again on the decline. Through games of June 1, the league posted a .288 BABIP. Even if you were to brush that off as a small sample anomaly, that rate is in a massive hole. It would take an offensive explosion I think we can all agree that isn’t going to happen in order to bring that BABIP back up to even close to where we saw it just a few seasons ago.

At Baseball Prospectus, Robert Arthur has a hypothesis as to why BABIP has tumbled the last couple of years.

Although it’s hard to prove definitively, improved defensive tactics look like they may be partially to blame for the historic falloff in BABIP. Just as batting average was drying up, teams look to have been repositioning their fielders across the board, pushing nearly every position back a few steps. The positions that moved back most—third basemen and center fielders—appear to be responsible for almost the entire decrease in BABIP in the last few years.

The positioning data says that center fielders have collectively been playing deeper, moving back by 11 feet from 2015 to 2021. Third basemen are back by eight feet. Arthur found that this movement back at these two positions correlated with a steep decline in BABIP, which is impacting the league-wide numbers.

In fact, the real change is even more amazing: balls hit to third basemen and center fielders have dropped by almost 40 points of BABIP since 2017 (and 40 points of wOBA). Balls hit to literally every other position on the field have barely budged over the same timeframe, increasing BABIP by .003 and wOBA by .006. The two positions with the largest changes in where they stand are responsible for nearly the entire improvement in defense since 2015.

Let’s revisit that first chart, but this time the Royals’ pitcher’s BABIP allowed will be included.

Kind of wild how this works. In the years where the Royals were better than league average on BABIP allowed by their pitchers, they were winning. The years where they were trailing, they weren’t. They also largely followed the league trendlines from 2018 to 2020. This year, even though BABIP is down overall, they’re holding steady with a .303 BABIP through their first 53 games.

How does this relate to their fielder positioning that Arthur is discussing? Let’s start with center field. The Royals have a ton of acreage in the Kauffman Stadium outfield and with that much territory to cover, we can maybe assume they will have an above-average BABIP on balls hit to that position. But Lorenzo Cain!

Royals pitchers used to have a below-average BABIP on balls hit to their center fielder. Things changed in 2018 once Cain departed. It didn’t seem to matter if he was playing a shallow center like in 2015 or a little deeper like in 2017.

Since Cain’s departure, Royals pitchers have yielded a BABIP above the league average on balls hit to center. And while the league is overall playing a deeper center field, Michael A. Taylor has moved in several feet from where Royals center fielders were playing the last couple of years. Historically, he’s played a little more shallow in center. Perhaps that’s where he’s the most comfortable. And he’s kind of decent going back.

While Taylor is playing a shallower center, the BABIP against Royals pitchers on balls hit to that position has declined. While positioning matters, personnel is perhaps a little more important when it’s broken down to an individual team level. Especially on a position as important as center field.

Let’s look at third base and how the Royals fare against the league averages in BABIP and positioning.

As in center, Royals’ third basemen have crept in a little bit in 2021, going slightly against the league averages. The impact of playing in at third is less than in center for obvious reasons. However, historically, balls third basemen in Kansas City have a higher BABIP than league average. The outlier season was in 2019 when Hunter Dozier played most of the innings at the hot corner. He’s played the most innings at third thus far in 2021, but with the time he’s missed, it certainly hasn’t been a majority. If Dozier can stay healthy and spends most of his time at the hot corner, it will be interesting to track BABIP on balls hit to third. Will it decline from where it stands currently?

From the data, it’s impossible to draw a clear conclusion between positioning and how it impacts BABIP on a team level. In Kansas City, they’ve largely followed the league-wide trends of positioning their fielders (particularly in center and at third) further back, although they have moved in a bit from last year, but the impact on BABIP seems to depend more on the personnel than position.

Still, defensive positioning continues to matter. We see the infield shifts and can immediately note the results of a batted ball to determine whether or not the positioning was correct in that situation. When a fielder edges back by a few feet, it’s a subtle adjustment but one that can also carry an impact.

I’ll continue to keep an eye on the numbers and positioning as the season progresses. As the overall BABIP continues to stabilize, it will be interesting to see how the data evolves. If it evolves at all.

Central issues

Twins 3, Orioles 6

As the Twins fly into Kansas City, they’re slumping yet again. Since sweeping the Orioles at home last week, they’ve dropped two of three to the Royals and now to the O’s in Baltimore. It was the first time the Orioles won a series at home since last September.

Matt Harvey started for Baltimore and went three innings of one-run ball. The bullpen finished it off, allowing just two runs over the final six frames.

Meanwhile, the Twins injury list continues to grow. They lost Rob Refsnyder to a concussion and Mitch Garver with a groin contusion earlier in the week and on Wednesday reliever Caleb Thielbar exited with a mild groin strain.

White Sox @ Cleveland — PPD

Washout in Ohio means the teams will make up the game in late September. Think about seven inning doubleheaders in a potential pennant race. Thanks Mr. Manfred!

Up next

The banged-up Twins arrive in Kansas City for a four-game set. The only officially announced starter for the Royals is Kris Bubic on Thursday.

Thursday—JA Happ vs. Kris Bubic

Friday — Matt Shoemaker vs TBD

Saturday — José Berríos vs TBD

Sunday — Michael Pineda vs TBD

With the Royals hovering around .500, it feels like every series within the division can be classified as “key.” With the Twins struggling again, it’s a perfect opportunity to create even more separation between themselves and the early season favorites.

Those are some interesting numbers. Especially the impact of increased depth at just those two positions.

Without examining the numbers I would assume that the reduced BABIP is mostly due to the shift and hitters simply refusing to bunt/hit opposite field, etc.

I would be interested to see what the BABIP is on balls hit opposite of the shift vs. towards the shift.